2018 brought a rare breakthrough for the Earth when governments, nonprofits, and individuals came together to curb humanity’s insatiable appetite for plastic. Plastic pollution was selected as the theme for Earth Day and the UN’s World Environment Day; National Geographic has declared 2018 its year of #PlanetOrPlastic; and #plasticfreejuly–a movement started in 2011 from just a handful of participants in Western Australia–has turned into a global movement.

But a tone-deaf and more significantly, unrigorous article published in The Economist appears to contradict all that by suggesting that plastic pollution “is not the Earth’s most pressing problem” and that “the trouble is, it’s so useful.”

The Economist downplays the toll of plastic on the Earth, noting that just 10% of 3.6m tons of solid waste discarded each day around the world is plastic. Whether you think that that is a significant number depends on how you frame it: 10% of your daily calories might not make or break your diet, but how about 10% of the critically endangered black rhinoceros? To millions of marine animals, 10% is a number with life-or-death stakes. And when 10% translates to 360,000 tons of waste, the vast majority (79%) of which ends up in landfills or in the oceans, that is an astronomical number–especially multiplied by 365 days a year, year upon year.

The article then notes that “if swallowed by fish, compounds in plastic fragments can be absorbed from the digestive tract into flesh. However, no studies have so far been performed to test whether such toxins concentrate up the food chain, as mercury does in fish.” It implies, therefore, that cost of plastic to human health must be negligible. It even casts a shadow of ambivalence on phthalates and BPA, (“they might disrupt [hormones] in high concentrations”) saying that “for decades both have been licensed for use in everything from pipes to shampoo bottles because human exposure was unlikely to exceed safe limits.” The Economist editors might be advised that the use of “might” is unconscionably misleading when there are scores of scientific studies that have linked these plastic substances to asthma, ADHD, breast cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes, low IQ, neurodevelopmental issues, behavioral issues, autism, altered reproductive development and male fertility issues. The decades of phthalates and BPA approval speak more to the efficacy of the lobbying by the Big Chemicals industry than to the innocuousness of these verified toxins. This is an oversight that goes past simple bad storytelling to lapse in journalistic ethics.

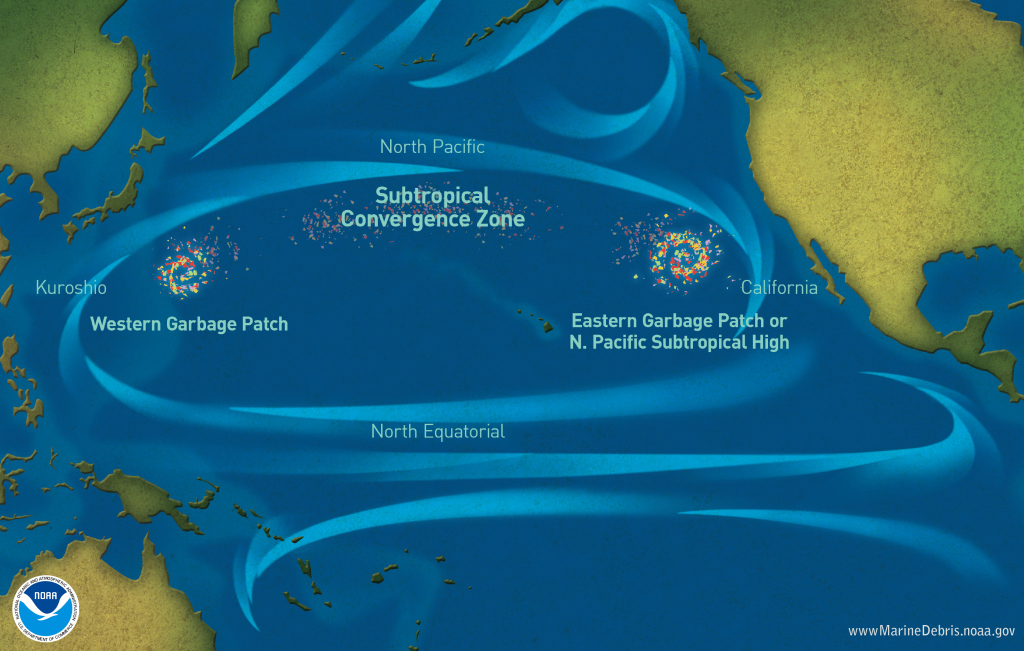

The Economist also claims that all “solid plastic waste produced since the 1950s that has not been burned or recycled […] could all have been dumped in a landfill 70m deep and 57 square km in area–that is to say, the size of Manhattan.” This is grossly belittling the size of the problem, considering that plastics have *not* been contained to an area and that there is currently a floating mass of plastic garbage three times the size of France in the Pacific Ocean (The Great Pacific Garbage Patch).

Great Pacific Garbage Patch Map

Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Litter and Plastic Bags in U.S. Wetland

Even that pales in comparison to the audacity of claiming that “the overall cost of plastic pollution compares favorably with other sorts of man-made harm,” saying climate change is the bigger threat. This is akin to claiming that “racism kills more people than gender inequality so the latter isn’t a pressing issue.” First, let’s affirm that efforts to curb plastic pollution and climate change are not mutually exclusive and that logically, the importance of one does not diminish that of the other. In fact, people who care about one issue are like to care about another issue. I’ve yet to meet a person who had modified her behavior over climate change who wasn’t also doing something about plastic, and vice versa. So inferring that if you prioritize climate change, you shouldn’t pay attention to plastic pollution is completely illogical.

In this vein of climate-change-first-mentality, the article argues that virgin plastic production releases 2-3 kg of CO2, equal to the amount released by steel and five times more than wood. Since plastic weighs less than other materials, the article posits that it is the more eco-friendly choice. Here’s the argument in full:

“A British government analysis from 2011 calculated that a cotton tote bag must be used 131 times before greenhouse-gas emissions from making and transporting it improve on disposable plastic bags. The figure rises to 173 times if 40% of the plastic bags are reused as bin liners, reflecting the proportion in Britain that are so repurposed. The carbon footprint of a paper bag that is not recycled is four times that of a plastic bag.”

If you carry a cotton tote bag around every day, as I do, you will refuse anywhere from 1 to 5 plastic bags a day. Many grocery and common goods stores double-bag, so this could be 2-10 plastic bags, realistically. Let’s just say you save 5 plastic bags a day–that means a cotton bag earns itself out in CO2 by day 27–less than one month. By the time the tote finishes its lifecycle in up to 10 years (I have a 6-year-old tote that’s showing signs of wear and tear after so many groceries, laptop, and gym clothes), it will have more than compensated for its CO2 production by a factor of dozens to hundreds.

It also notes that the “carbon footprint of a paper bag that is not recycled is four times that of a plastic bag”–but conversely, that just means a paper bag has to be reused 3 times to match the climate change impact of a plastic bag. This is not a terribly difficult thing to do, if you reuse your paper bags for bulk food section, to take out recycling, and to transport your vegan lasagna to your friend’s dinner party, etc. Afterward, you can recycle or compost your bag–neither of which is possible with plastic bags*. Moreover, you can’t measure environmental impact by CO2 production alone, and paper bags have an innate advantage to plastic bags by being 100% biodegradable and toxin-free. If left out in nature a paper bag will disintegrate rather quickly, will not choke, strangle, or starve any pelican, albatross, whale, turtle, seal or fish. Meanwhile, “estimates for how long plastic endures from 450 years to forever,” according to National Geographic. Of course, we don’t know exactly how long it will take because plastic hasn’t even been around that long. And that’s part of the horror.

The article goes to extol the virtues of plastic: “By keeping food fresh for longer, plastic packaging substantially reduces organic waste, itself a growing environmental concern. In 2015 J. Sainsbury, a British grocer, reduced waste in a beefsteak line by more than half by using plastic vacuum packaging.” Actually, the best food for both human and planetary health does not come in plastic. Not only is plastic packaging leaching BPA, phthalates, and other obesogens into your food, packaged foods, in general, are highly processed, loaded with preservatives, oils, sugar, and other unhealthy substances. Fresh food comes in nature’s packaging: fruits and vegetables, which makes up 90% of my groceries as an organic, reduced-plastic vegan.

Since The Economist seems intently focused on climate change as the most important question of our day, I suggest that its editors stop endorsing plastic-wrapped beef as an eco-friendly innovation and adopt a vegan diet, which cuts an individual’s carbon footprint by 73% according to a study published in Science. A vegan diet is the single most impactful thing you can do to curb climate change–more than driving an electric car, more than forgoing air travel, obviously more than choosing plastic bags over a cotton tote, as The Economist will incorrectly have you believe.

Finally, the editors of The Economist, I suggest you take a look at your own cotton tote bags at your online store. The tote chirps: “An ideal book bag, or even just something to take along to the farmer’s market. Use as a shopping bag, gym bag, work bag, beach bag, school bag, laptop bag, shopping bag, everyday tote bag and many more! Re-usable – can be used over and over again.” So are you saying it’s eco-friendly? Do you see the irony here? Stay consistent with your message, The Economist. Don’t write shoddy, logically and ethically unsound articles. If you really believe cotton totes are such anathema to climate change efforts, take these things off your site. And please, think responsibly.

__

Related: Pacific Garbage Patch Is 100x Bigger—#PlasticFreeJuly Needs You More Than Ever

Bonnie Wright Wants Muggles, Not Magic, To Fix Plastic Crisis–Her Eco Chic Decoded

12 Ways To Minimize Your Plastic Footprint & Feel So Much Better About The Turtles

__

Photo: Katy Belcher on Unsplash, Wikimedia Commons, ORCA Ocean and Reserve Conservation alliance, Midway Atoll Refuge via Flickr, The Economist